A small write up after the first session with Sheldon Brown.

Cutting across somewhere between in the scalable city — Bruce Sterling

Scalable City in itself is an interesting project in that at it’s core this idea of scalablity means it’s doesn’t fulfil a single purpose. It truly is scalable in that as an “artifact” it can be observed at different scales (big/small, close/far), and also in a more technical sense it allows it to grow as the technology which drives it develops.

Bruce Sterling in his write-up essentially tries to find a suitable language with which to talk about the piece after claiming that “neo” this, “hyper” that are not appropriate ways to help us understand the work.

If we dig deeper into the discourse of computational aesthetics - and it has one, though it’s small and peculiar - we hit a neologism called “processuality.” Deleuze and Guattari - I hate to drag those two in here, but they did in fact use this term quite early - claim that “processuality” is the antithesis of “arborescence.” “Arborescence” is a static, tree-like hierarchy trying to exist in the world as a single, well-defined stable entity, while “processuality” has something weird going on. Carefully crafted layers of paint, in a frame, curated and hung on a gallery wall that has arborescence. Software has “processuality”. Software is electricity flowing through circuits, algorithms being executed. The aesthetic look-hear-and-feel of software as it scampers through its repertoire of behaviors is its “processuality.”

Something which possesses processuality (or, process) is something which is never quite fixed, or determined. Sterling uses the example of a Calder mobile. Scalable City is supposedly a good example of a digital work with processuality as it behaves in a fashion which is not jarring or unnatural (in it’s physics and general simulation). Thus creating an experience which flows.

In general I’m not a big fan of what I see as making up words to describe something. I think that is where art becomes art for intellectuals. Which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, I don’t think, but not really somehting I’m interested in. But I do appreciate the value of a seamless, easy experience for a “user”. I experienced the opposite at the AI exhibition at the Barbican it made the whole experience frustrating and disappointing.

Grayson Perry: in defence of super-rich knick-knacks

It seemed like an opportunity to examine my relationship with the art market, and collectors in particular. One of my favourite quotes comes from Nam June Paik, the video art pioneer: “An artist’s job is to bite the hand that feeds him, but not too hard.” So the works in this show may be a little unsettling, but also — hopefully — seductive and covetable.

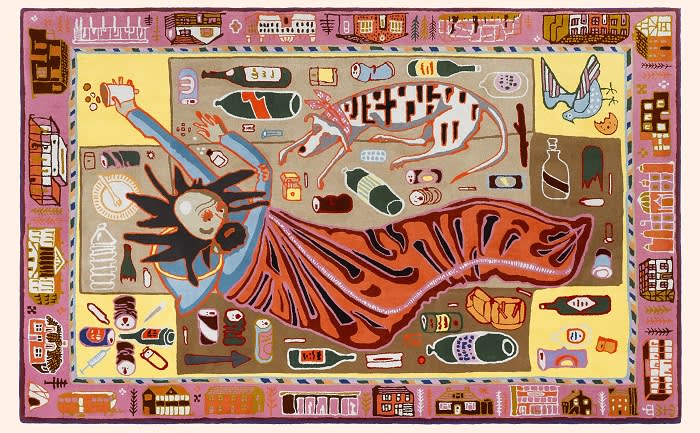

“Large Expensive Abstract Painting” is a computer-controlled weaving that virtually mimics the hands-on process of the sticky, smelly painter. The “base” is a collage of traditional fabrics from around the world. On top of this I have digitally “splodged” the oh-so-expressive “paint”. Over that, I have laid a schematic map of London, spiritual home to so many of the world’s super-rich. Finally, I “pasted” a series of labels, hinting perhaps at the social forces, tastes and codes that might lead to someone understanding (“Elite University”); desiring (“Unregulated Market”); buying (“Rent Seeker”); and displaying (“Super Cars”) a “Large Expensive Abstract Painting”.

Some of what Perry talks about resonates with my opinions of art and the art world generally. I’d like to think I was trying to make work in a similar way some years ago, but without the potential super-rich buyers. It’s hard not to get annoyed at someone critiquing the market in which they exist and contribute to. But it’s also hard not to sympathise and think: fair enough. He is existing in a market, which exists within the bigger framework of capitalism, of which we are all a part of. He has found a way to critique, and make a good living. I do think however, the fact that Perry and his work try to sit on both sides of the fence, sucks the impact out of the work a little bit. I can appreciate it, and find it funny and interesting, but I don’t see how it’s contributing to change very much.

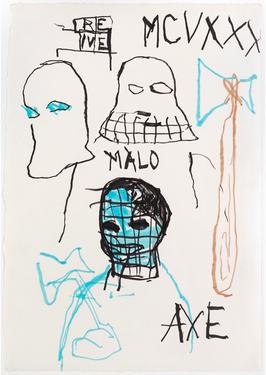

I don’t quite know what I think constitutes “good art” in any context, but I like that art is a thing — I like that it’s there. I think I only appreciate art when it’s looked at as something that has already happened. I can appreciate seeing Basquit paintings riddled with politcal messages, in a time where he (as a black man) was probably ostracised and unappreciated, in the art world at least. But I don’t think that really works at the time. I don’t think you can intentionally create an “art” to shake up societal views of race or gender (for example). That “art” can only be appreciated once those soceital view have since progressed, and your art can be seen as radical and ahead of it’s time.

From the Basquiat Wikipedia page:

Basquiat used social commentary in his paintings as a tool for introspection and for identifying with his experiences in the black community of his time, as well as attacks on power structures and systems of racism. Basquiat’s visual poetics were acutely political and direct in their criticism of colonialism and support for class struggle.

During the early 1980s, Basquiat made his breakthrough as a solo artist. In June 1980, Basquiat participated in The Times Square Show, a multi-artist exhibition sponsored by Collaborative Projects Incorporated (Colab) and Fashion Moda where he was noticed by various critics and curators. In particular Emilio Mazzoli, an Italian gallerist, saw the exhibition and invited Basquiat to Modena (Italy) to have his world first solo show…

I can’t help but see that story as: a wealthy white gallerist seeing the financial gain in taking on a young, black, politically active artist. Sure Basquiat got rich too and Basquiat’s transition from being homeless and unemployed to becoming a prosperous artist took place in a short space of time. By 1980, he would be selling a single painting for up to $25,000. But I can’t imagine he was feeling particularly fulfilled given that he died of an overdose at 27. I guess what I am grappling with is that Basquiat’s work is important, as is Grayson Perry’s, because they do provide a commentary of the times in which they exist, but in order to filter into the mainstream where it will actually get seen, they need to somehow exist in this framework of art as a commodity where it can only pass hands between the super rich. And by doing so, maybe, it loses it’s political value, but gains capital value.

NART

This pretty much brings me to the title of this post, NART. NART is a concept introduced (conceived?) by Sheldon Brown in our first session with him. NART is Not ART, as NAND is Not AND. The analogy is a little bit tenuous, unless I’m missing something, but I like that the NAND gate is the fundamental building block of all computing, and is substrate-independant, meaning the logical process of input and output is not limited to electronics; it is possible to make entirely analogue NAND gates, and therefore entirely analogue (or biological or otherwise) computers. I guess the connection is concept of negation within the name.. I dunno. But what I do like is the word, NART.. Not ART. And I’m starting to think that ART becomes NART as soon as it enters the gallery.

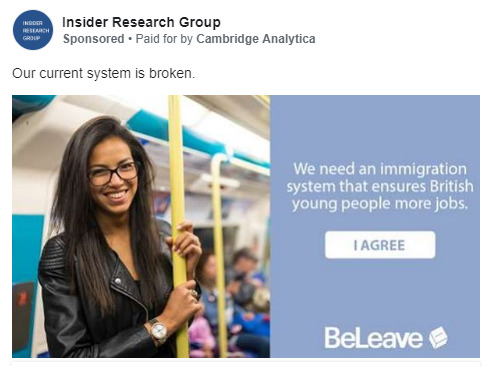

Some ART THOUGHTZ I’ve been having for a while now, are that I think the most impactful ARTZ in the world right now are the ones which exist outside of the gallery, whether they are trying to be ARTZ or not. Some examples below:

There are more and more, but what they all have in common is that they are a commentary of the times in how they operate, the medium they use or the message they carry. But unlike self-proclaimed ARTZ, they exist in the public sphere and only work when they are directly engaged with by the public.

This is something I want to explore furthur, and drawing distinctions between the art world and the non-art world seems like a nice starting point, but I don’t want to dwell on “what is art” for too long.

Josh