This was written for the ‘Computational Thinking and Critical Practice’ class while studying on the Creative Computing Msc the Creative Computing Institue in 2020.

Practice Makes Perfect

Cultural Transformation as Brought About by our Computational Condition

Ray Kurzweil quite rightly said “ours is the species that inherently seeks to extend its physical and mental reach beyond current limitations”1. Through- out all history humankind has sought to improve its quality of life and ability to sustain its existence through experimentation, analysis and technology. Yuval Noah Harari outlines human development as a series of revolutions—cognitive, agricultural, scientific—each of which acted as catalysts, rocketing cognitive development of humans towards the next revolution2.

As civilisations emerge over time, and societies become more complex with economies, governments, religion and other strange human creations; progress itself became an intentional feature of civilisation and a focus on science and technological development emerges. The industrial revolution gave humankind new technologies with which to spread knowledge, travel and conquer3, feed- ing back into the system of development. Alvin Toffler, writing in 1965, con- templates the immediate future ahead of him, and is worriedly aware of the rate of progress. Worried enough to use the term “Future Shock” to describe the “super-imposition of a new culture on an old one” brought on by the “greatly accelerated rate of change in society”4. Pointing to very modern technologies of the time such as air flight, television, nuclear energy, the computer and the codification of DNA, Toffler proclaims that “what is happening now (in 1965) is anything like ’normal’ progress”.

Kurzweil similarly is aware, but slightly more excited by, the increasing rate of development human kind is experiencing. He points out that it is only now (in 2005) as we find ourselves at the knee of the exponential curve of growth that we can get a sense of the rapidity of progress. “We won’t experience one hundred years of technological advance in the twenty-first century; we will witness on the order of twenty thousand years of progress.”1

The increase in computing power, and the ubiquity of computing at large has been the latest and most powerful stimulant for progress, kicking us into the “knee of the curve”. These tools are far more powerful today and show great potential in all areas of science. The availability of Graphics Processing Units (GPU) along with seemingly unlimited digital storage and a flood of data collected from every possible source has allowed artificial intelligence research to explode in recent times, entirely reversing the doubts of AIs capabilities leading to the so-called AI Winter5 of the 1980s. The commercial applications of AI in things like market analysis, predictive services and efficiency gains in logistics contributed to the financial boom in AI. DeepMind, a London based AI firm, was acquired by Google in 2014 for £400-million6 and in 2016 AlphaGo (an AI system designed by DeepMind to play the ancient Chinese game of Go, a game which has 10170 possible board configurations) beat the worlds leading player Lee Sedol—a landmark event in AI development.

Kurzweil sits among many other powerful players in the modern technology scene (Musk, Tegmark, Harris, Bostrom etc.) most of which are aware of this alarming rate of development7. So much so that Max Tegmark founded the Future of Life Institute which exhibits the tagline “Technology is giving life the potential to flourish like never before … or to self-destruct. Let’s make a difference!”8 We are very much living in the time period that Toffler was speculating of and it has been named the Anthropocene: the epoch of time Homo Sapiens became the single most important agent of change in the global ecology9. Arguably this has been the case for centuries, but the current climate crisis is hard-to-ignore evidence of this human impact drifting out of control. So perhaps these experts are worried for the right reasons?

Writing in 1965, the same time as Alvin Toffler, Donald Judd is noticing strange patterns emerging in the art world. Artists, largely considered painters, are producing what could be considered paintings, but seem to embody three- dimensional qualities. The work of Clyfford Still, Barnett Newman, Ad Rein- hardt and Kenneth Noland seems to exist on a two-dimensional plane but can be “both flat and infinitely spatial” or “give the appearance of sections cut from something infinitely larger”10.

Fast forward 55 years to the present day I would argue Judd’s uncertain comprehension of what he sees before him is even more apparent now. We are confronted with strange objects (to re-appropriate Judd’s terminology) every day in the form of fake news, deep fakes and unusual algorithmic artifacts as we communicate with one another alongside bots, watching our language so as not to become flags for their devious automated systems (see figure 2). Perhaps this is the Future Shock Toffler spoke of.

Today’s artwork too is dealing with equally strange phenomena. Like Judd, I see artworks which seem to exhibit qualities far greater than the sum of their parts. Olafur Eliasson experiments with perception and explores the limited facilities we have with which to understand the world. In the various iterations of Room for One Colour Eliasson has used monofrequency light bulbs to cast intense yellow light, in doing so overwhelming all other frequencies of light so that all we perceive is yellow and black. A truly unusual experience putting you as the observer in what feels like a parallel universe. The illusion is bro- ken as someone opens their phone, illuminating their own face in the artificial, polychromatic light of the screen.

Troika, a collaborative contemporary art group, has a “a particular interest in the subjective and objective readings of reality and the various relationships we form with technology”11. The artwork Dark Matter exists as three separate forms simultaneously. Depending on the observer’s vantage point, the piece takes the form of a square, a circle or a hexagon, or indeed somewhere between the three. This artwork is part of an ongoing exploration of perspective through sculpture where they use perceptual tricks to transform a three-dimensional object into a two-dimensional shapes. These tricks take advantage of quirks in the way humans take in visual information, and the mere fact that our senses can be tricked.

The aforementioned artworks are particularly interesting to me as they are so simple. Given that the methodologies they employ are far from hi-tech, the experience of the artwork is generated by the interaction between the piece and the (human) observer. This notion of understanding through perception is one which has undeniably framed all human endeavour given that we have no other option than perceive things as human. The implications of this are only becoming apparent thanks to the most recent nudge along the exponential graph of progress as computational power in scientific research has in fact revealed how little we truly know about the world.

Computation led the Cybernetics movement through the late 20th-century as the systems theories being developed by the likes of Jay Forrester could now be tested. Forrester was convinced that the world was made up of models, even “a mental image is a model” and suggested that “any concept that can be clearly described in words can be incorporated in a computer model”. It was merely a matter of obtaining enough data and in 1995 Forrester believed that “we now do know enough to make useful models of social systems”12.

The Modernist era was defined by this methodology. Humans have always sought to understand the world in which we live via the tools we have to observe the world, such is the cycle of technological development and scientific progress: “For Descartes, both the world and knowledge are transparently knowable, and the world is to be remade in the image of our knowledge of it: the most typ- ical feature of modernism in every field”13. The extreme rates of progress we are currently living in which excites and unnerves some the greatest experts in their fields is revealing as many unknown unknowns as it is converting known unknowns into known knowns14. In the same ways that the art- works mentioned above and the artworks Judd is so intrigued by, even in the simplest of objects can exist an indescribable complexity.

Developments in the world of science itself seem to highlight the failure of the Modernist methodology perfectly. It seems as though the finer grain detail in which we are able to model the natural world, the worse the models per- form. George Van Dyne led the Grassland Biome study in 1967 which aimed to scrupulously collect data of a grassland in Colorado and use this data to create as accurate a model as possible. The model which went through various iterations returned wildly inaccurate results. The process was “closely patterned after Forrester”15 and inspired by the work of H.T. Odum whose similar work was producing electrical models of natural systems. Forrester and Odum’s models however were drastically simplified and in leaving out many details, the models seemed to yield better results. “The modelling of the Grassland Biome, however, focussed increasingly on the production of the models themselves and thereby explicated ecosystem principles rather than questioned them.”15 Van Dyne was trapped in his vision of the world, through the lens of unbiased scientific enquiry, led by the computational tools at his disposal.

Research in AI and machine learning seems to be following the same trend of the Cybernetic system dynamics12 experiments which posits that if we have enough data, we can model anything. I do not wish to point at the failures of scientific exploration and use this to extrapolate my own trend lines to predict future failures. I do think however that there is a fallout from these explosions of rapid research which is landing back on the world of the arts, philosophy and humanities and is shaking up these fields of research as much as AI is shaking up the sciences.

Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO) is a relatively new school of philosophical thought which “believes that reality is mysterious and magical” and through the writings of Harman, Bogost, Morton and others, attempts to provide a “new theory of everything”13. Although computation itself does not often directly influence the humanities, the effects it has on the wider world still filter through and becomes an indirect influencer, much like the OOO belief that “beings influence each other aesthetically, which is to say at a distance”16 (beings here are not restricted to human beings). And thus the complex flows of system dynamics (or whichever mode of thought one wishes to take on) can feed back into one another: “Scientists are now beginning to figure out something we’ve known in the humanities and arts for some time: one is entangled with the data one is studying.”16 (perhaps something that Forrester, Odum and Van Dyne did not realise in their time).

The sciences are often deemed entirely separate from philosophical thought, given that science is (by definition) based on empirical evidence. But the em- pirical evidence of study at fine grain detail can often reveal mysterious and magical results. “Quantum theory blew a huge hole in the idea of particles as little Ping-Pong balls. Relativity destroyed the idea of consistent objects: things that are identical with themselves and constantly present all the way down.”17 Science is as subjective as philosophy or the arts and is not immune to being framed by the human interpreter, for better or for worse. A philo- sophical interpretation of the sciences is as good as a scientific interpretation of philosophy.

Scientific attempts to understand such complex phenomena as the aesthetic experience of art have oftentimes shown how far away science is from absorbing the arts as something which can be described in terms of bits or atoms. Neuro- scientist V.S. Ramachandran has attempted to develop a science of the visual arts (or “Neuroaesthetics”) through experiments using brain imaging techniques (fMRI) and studies with people who were born with, or have suffered from neu- rological afflictions. Ramachandran attempts to apply the peak shift effect (a principle in animal discrimination learning) to the human experience of the vi- sual arts suggesting that humans have a visceral response to the overall shapes and figures on display, disregarding the details. Ramachandran looks at the “ac- centuated hips and bust” in the 12th-century bronze sculpture of the Goddess Parvati. He suggests there are neurons in the brain which are reactive to “sen- suous, rotund feminine form” and in amplifying these details in the sculpture the artist is unknowingly creating “super stimuli” which trigger the relevant neural-networks in the brain. He goes on to suggests similar effects are created in more abstract forms as seen in Cubism, or even the sunflowers of Van Gogh: “the visual neurons that represent colour memories of those flowers even more effectively than a real sunflower or water lily might.”18

Ramachandran has come under a lot of scrutiny for his paper with oth- ers criticizing his oversimplification of the aesthetic experience overlooking the “contributions of emotion, intention, memory, and knowledge”19. Alva Noë is someone who tackles similar topics of perception, consciousness and theories of art but from the vantage point of philosophy. Noë suggests that the “neurosci- entific approach is too individualist, and too concerned alone with what does on in the head”20. Along similar lines of the OOO school of thought, Noë does not take phenomena specific to human existence at face value and assumes that there is more at stake than a deterministic set of processes. In contrast to the neuroscientific approach, Noë offers that “art can help us frame a better picture of our human nature.”

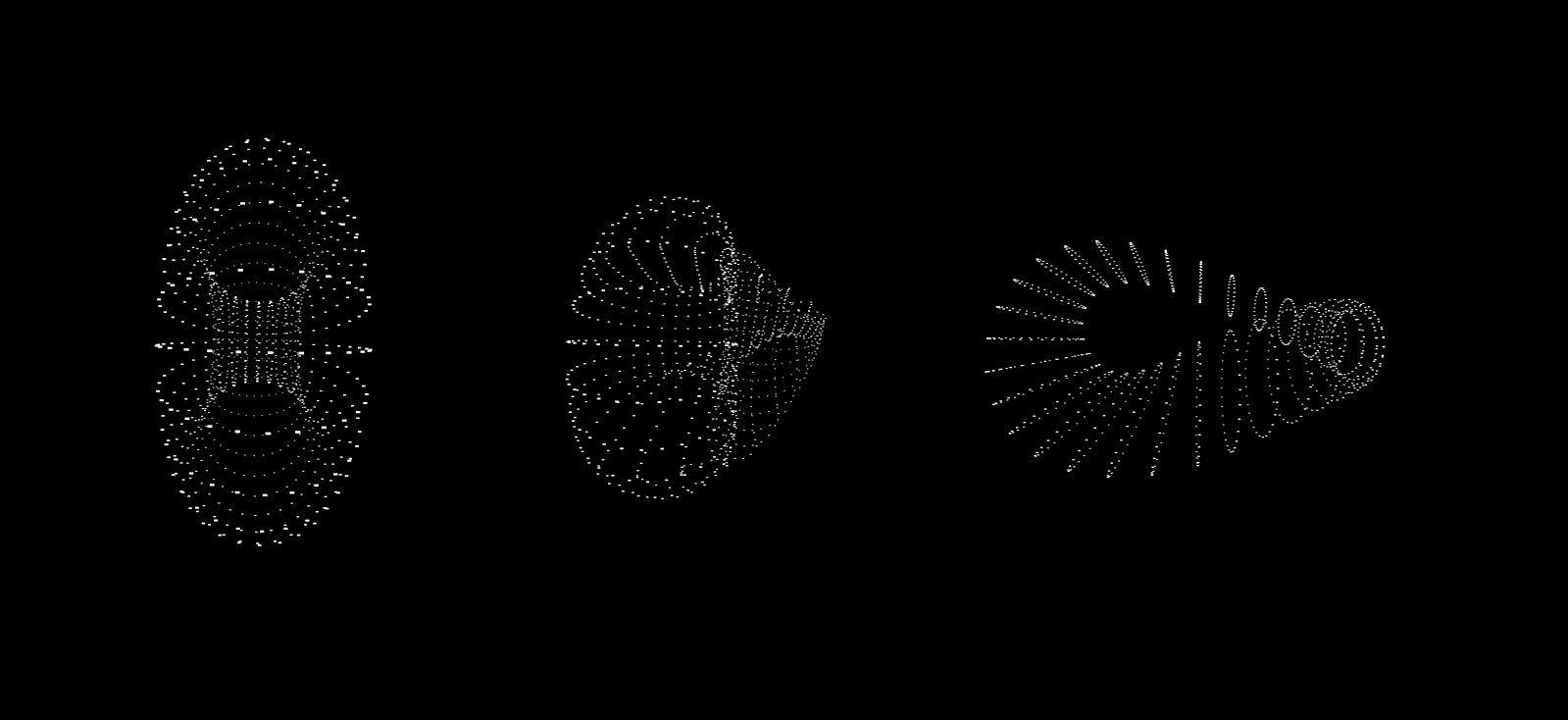

As a subscriber to the OOO school of thought myself, I appreciate there is a lot to think about at once. There is not a linear, causal relationship between any two things. I find myself moving between the science-led, empirical evidence kinds of thought, to the more aesthetic, relational kinds of thought. For the same reason I tend not to call myself an artist, or a designer, or an engineer; but I do agree with Noë when he says “making stuff is special for us.”20 I am interested in computation and much like Forrester I want to use computers for what they are good for: computation. A computer at its core is a simple machine, turning miniscule switches on and off. Compounding these tiny switches into deliberate arrangements allows for computation to occur. Abstracting this process and allowing chunks of switches to represent symbols soon develops into a complex system capable of demonstrating what some people believe is magic. I prefer to think on the computer’s terms; not quite in 1s and 0s, but at least in coordinate systems and memory. My naïve experiments in generating and manipulating forms parametrically are an attempt to understand space as a computer does: as lists of numbers (see figure 5). When learning to paint I would restrict my palette to the same 5 colours; this taught me more about light, tone and contrast than if I had every colour under the sun. My digital palette is geometry and linear algebra—I am trying to think in ways which complement the computer’s structure, whilst understanding it’s limitations.

Whether one works in the humanities or in the sciences—as we continue along the exponential curve of progress and understand more about the world we live in, the tools we have become more sophisticated and the information richer. However the ways in which we frame this information and give it meaning will always be human. The human thirst for knowledge has been an ongoing cycle of humiliations in which a well defined theory of the world gets displaced by peering through the cracks at what has been overlooked—a Copernican Revolution. Morton proposes that OOO will provide the next displacement of the human “by insisting that my being is not everything it’s cracked up to be” or rather that “the truth of Copernicanism …is that there is no center and we don’t inhabit it”.17 Like Kurzweil I am excited by what the future brings. The rate of progress is fast and I expect to see great achievements in my lifetime; I am excited to see what else we do not know.

References

-

Ray Kurzweil. The Singularity is near: when humans transcend biology. London: Duckworth, 2006. ↩ ↩2

-

Yuval Noah Harari. Sapiens. Penguin, 2011. ↩

-

Jeremy R. Lent. The patterning instinct: a cultural history of humanitys search for meaning. Prometheus Books, 2017, p. 324. ↩

-

Alvin Toffler. “The Future as a Way of Life”. In: Horizon Magazine (1965). url: http://www.benlandau.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/ Toffler-1965-The-future-as-a-way-of-life.pdf (visited on 03/09/2020). ↩

-

Micheal Copeland. What’s the Difference Between Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and Deep Learning? https://blogs.nvidia.com/ blog / 2016 / 07 / 29 / whats - difference - artificial - intelligence - machine-learning-deep-learning-ai/. 2016. (Visited on 03/10/2020). ↩

-

Samuel Gibbs. “Google buys UK artificial intelligence startup Deepmind for £400m”. In: (2014). url: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/ 2014 / jan / 27 / google - acquires - uk - artificial - intelligence - startup-deepmind (visited on 03/13/0020). ↩

-

Future of Life Institute. Superintelligence: Science or Fiction? — Elon Musk & Other Great Minds. 2017. url: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=h0962biiZa4. ↩

-

Future of Life Institute. Future of Life Institute. 2016. url: https : / / futureoflife.org/. ↩

-

Yuval Noah Harari. Homo Deus. Penguin, 2015, p. 84. ↩

-

Donald Judd and Thomas Kellein. Donald Judd. D.A.P., 2002. ↩

-

Eva Rucki, Conny Freyer, and Sebastien Noel. About Troika. https:// troika.uk.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/200228_TroikaCV- 1.pdf. (Visited on 03/10/2020). ↩

-

Jay W. Forrester. “Counterintuitive Behavior of Social Systems”. In: SIM- ULATION 16.2 (1971), pp. 61–76. doi: 10.1177/003754977101600202. eprint: https://doi.org/10.1177/003754977101600202. url: https: //doi.org/10.1177/003754977101600202. ↩ ↩2

-

Graham Harman. Object-oriented ontology a new theory of everything. Pelican, an imprint of Penguin Books, 2018. ↩ ↩2

-

U.S. Department of Defence. DoD News Briefing - Secretary Rumsfeld and Gen. Myers. 2002. url: https://archive.defense.gov/Transcripts/ Transcript.aspx?TranscriptID=2636. ↩

-

Chunglin Kwa. “Modeling the Grasslands”. In: Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences 24.1 (1993), 125–155. doi: 10.2307/ 27757714.7 ↩ ↩2

-

TIMOTHY MORTON. DARK ECOLOGY: for a logic of future coexis- tence. COLUMBIA University Press, 2018. ↩ ↩2

-

Timothy Morton. Hyperobjects: philosophy and ecology after the end of the world. University of Minnesota Press, 2014. ↩ ↩2

-

Vilayanur Ramachandran and William Hirstein. “The Science of Art: A Neurological Theory of Aesthetic Experience”. In: Journal of Conscious- ness Studies 6 (Jan. 1999), pp. 15–51. ↩

-

Mengfei Huang. “The Neuroscience of Art”. In: Stanford Journal of Neu- roscience 1 (2009), pp. 24–26. ↩

-

Alva Noë. “What Art Unveils”. In: The New York Times (2015). (Visited on 03/11/2020). ↩ ↩2